It is my pleasure to provide my friend an opportunity to bring us rich history from the southern area of Sussex County. I know you will be entertained by the knowledge of historian Rich Vohden.

The Bango Forge is on Pequest Road at the Pequest River.

About 1750, Thomas Wolverton, a 33-year-old shopkeeper from Bethlehem, Hunterdon County, came to Huntsville, where he acquired 91 acres that were deeded from Sam Green “to be taken up and surveyed in any part of West NJ.”

Wolverton may not have known it at the time, but he cheated a little and settled just one quarter-mile east of West Jersey.

Here, where the Pequest River and the main road between New York City and Easton intersected, Wolverton built a tavern and inn, which in 1756 served as the location for the Sussex County Court. But courts were routinely unable to meet because of ongoing Indian hostilities, part of the French and Indian Wars.

This site was the only location in the are offering the high banks needed to build a large dam high enough to create Brighton Lake, allowing the power of the flowing water to be effectively channeled through a millrace to power a gristmill, a sawmill and eventually the Bango Forge.

How Wolverton heard of the iron deposit in Andover is unknown, but after he learned that the red hematite ore, comingled with magnetite, was “esteemed of the best quality in America,” he built the forge on the south side of the river.

He built a unique bloomery forge that used a waterwheel to power bellows to blow air into a very hot fire and work super-heated iron ore into a white-hot mass known as a “bloom.” A hammer, also powered by the waterwheel, then shaped the ore into a bar while pounding out any impurities.

The iron ore that was processed in the forge came from a mine in what is now Andover, on Limecrest Road opposite the entrance to Aeroflex airport.

The mine was located on William Penn’s Tract No. 35, owned by two sons of William Penn.

The Bango Forge earned its name from the incessant banging of the 500-pound trip hammer that was lifted by waterpower and released to fall on the bloom, creating a sound that could be heard for miles around.

Snell’s History of Sussex County records that the local people said the hammer repeated “‘come penny, go pound,” referring to the fact that the forge was not turning a profit.

The forge operated for only a couple of years. Maybe it wasn’t established to be profitable.

Now for the intrigue, and the rest of the story.

The following facts are from the history books and the legends and stories passed down to me by my neighbors Walter Smith (1899-1993) and Bill Morris (1913-2004), both born and raised in Huntsville.

Bloomery forges were usually owned and operated by “bloomers,” who were experts who handed down the secrets of the trade from father to son. Wolverton was not a “bloomer” and would have been foolish to gamble on such a venture by himself.

William Allen and Joseph Turner, who owned the Union Ironworks in Hunterdon County, sent iron masters and bloomers from Hunterdon County to operate the forge for Wolverton.

Allen and Turner were very prosperous businessmen from the same area as Wolverton in Hunterdon County. They had done business together in the past. (Allentown, Pa., is named for William Allen).

Shortly after the Bango Forge closed down, Allen and Turner used another partner to negotiate the purchase of the land with the mine from two sons of William Penn so that they, as owners of an ironworks, would not seem too anxious.

They purchased the property at a good price. It is not known if the Penns knew about the iron deposit.

In 1758, Allen and Turner organized the very successful and profitable Andover Iron Co. The rest is history.

I believe the Bango Forge was operated for the sole purpose of determining the value of the iron ore without the Penn family being aware of the value of the mine.

After the forge shut down, the building was used for many purposes. It served as a blacksmith shop, a wheelwright shop and an icehouse.

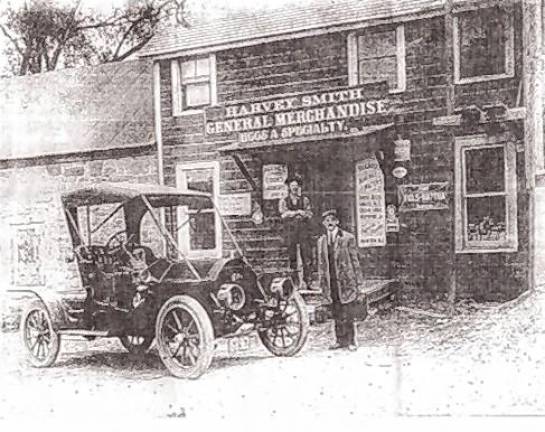

In 1846, the forge and the blacksmith business were purchased by I.A. Straley. At this time, a store was built and operated next to the forge.

Isaac’s son also ran the blacksmith shop until the Sussex County Railroad came through Sussex County; then he moved his blacksmith business to Andover. The name John Straley Jr. is carved into the limestone wall of the forge with the date 1907.

In 1870, the Post Office for Huntsville was established in this building, with Lewis Wilson as postmaster, followed by Issac Straley and finally by Harvey Smith until discontinued in 1926.

During this period, DeLancy McConnel was operating a blacksmith shop in the Bango Forge. It was told to me by Walter Smith that the two blond DeLancy sons went west to become cowboys.

DeLancy’s name also is carved in the limestone wall of the forge, as are many other names. I guess these guys had a lot of time on their hands.

The house next to the forge burned down in 1961, not long before the new bridge over the Pequest was built in 1966.

There have been many changes in Huntsville since 1750, but the Bango Forge still stands here to remind us of our local history.