Legendary Chief Irons ran things his own way

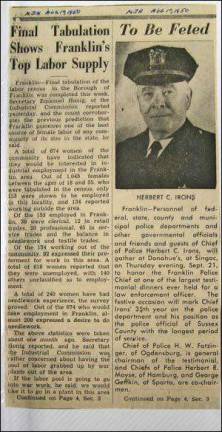

FRANKLIN If Robert Catlin was the man who saved Franklin, then Herbert C. Irons became the man who cleaned it up and tamed the “Model Mining Town of the East.” It’s been 50 years since the passing of the legendary Franklin police chief, but even today, there are many in Franklin who remember the not-always-so-gentle, yet deeply caring and dedicated man who watched out for Franklin in much the same way as he would have for his own family. “I had a lot of respect for the guy,” said former mayor Doug Kistle. “That was back in the day when he had full power to do whatever he wanted to do. He was a one-man band there, and he took care of the town. He had a strong voice and he was a strong man.” “He ruled this town with an iron hand,” recalled Joe Bene, a former New Jersey Zinc Co. employee who is today a trustee of the Franklin Historical Society. “He did things that you can’t do today. If you came in on the train and said you were going to see so-and-so, he’d say, That person doesn’t live here any more; get back on the train.’” In 1915, Franklin, only two years into its autonomy from Hardyston, was a rough-and-tumble mining town, which worked hard at removing the rich zinc ore deposit from the mines below, while also experiencing some of the political and emotional turmoil of the day. At the top of the list was the ongoing First World War, which became the topic of discussion among many miners, some of whom were not at all hesitant to take their debates further into the street, where some settled their differences with fist fights and other ungentlemanly methods. Because all of Europe and other parts of the world were at war, the fact that a lot of the miners here were of differing ethnic backgrounds made it virtually inevitable that discord of some kind would take place. Thus, on Oct. 1, 1915, a page one story in the long-since-defunct Sussex County Independent declared, “Believing that a two-fisted mounted man, who did not know what it was to be afraid, was the sort to handle the situation in Franklin, the borough council there has reached an arrangement with (Mr.) Irons of New York, a former United States army man, member of the (Panama) Canal Zone police and also of the Pennsylvania state constabulary, to constitute the mounted police force in Franklin, at $1500.” Simply put, Irons was, in the words of Bene, brought in “to clean up the town,” which he did and then some. That employment would go on to last 42 years, with Irons switching from horseback to motorcycles in 1919, and then to automobile beginning in 1922. Over the years, he had to deal with the ruffians of his day, some of whom subjected Irons to gunshot and knife attacks but who were made to pay dearly for their lawlessness. In particular, Irons became part of a force investigating and pursuing a ruthless robber gang. That group, while committing armed robbery on June 14, 1921, also shot and killed a man who had come to the aid of two men whose truck containing a shipment of silk was hijacked by a gang of six along the Cat Swamp, located along Newton-Stanhope Road. About two months later, during the apprehension of the gang, Irons and another man chased one of the suspects into a Pennsylvania barn. After the suspect wounded Irons’ partner, Irons returned four shots of his own, which wounded and halted the suspect, who later was executed in the electric chair. Yet, despite all of this heroic background of valor and violence, Irons was said to be “proudest of the fact that the children around the town considered him a pal,” reported another county paper on Nov. 6, 1958, shortly after the retired chief died in Florida from a sudden heart attack at age 68. “I found him to be a very fair man,” Bene said. “Years ago, when I was about 13 years old, I was a caddy at the Wallkill Country Club here in Franklin. And this particular week, I was assigned to be a brook boy’ on the fifth hole. I was talking to this young fellow and at the same time, a golfer hit a ball into the brook, which was the Wallkill River. And I went in and retrieved the ball out of the water, and I got either a nickel or a dime from the golfer. But when I came back out of the water, I went to my pants pocket the boy was gone and so was the money in my pants pocket. “So when I got home, I told my father, and my father and I went to the New Jersey Zinc Co. time office, and the clerk on duty notified Chief Irons. He came down to the time office and I told him what happened. He said to me, You get in the car’ and we went up to South Street, where the boy lived. The chief said, Stay in the car,’ and he went into the boy’s house. And a few minutes later, Chief Irons and the boy came out to the car, with the money and an apology. How’s that sound?” Mary Kistle, the former mayor’s wife of 49 years, also remembered Irons as a protector of women. “When my brother got his license, he drove through a puddle and didn’t think anything of it,” Mary Kistle said. “But he splashed some ladies nearby, and then Mr. Irons came to my father’s house and told him that if he ever did that again, he would take his license away. My brother didn’t realize he had done anything. Those were the days you could leave your door open night and day, and you didn’t have to worry about anything because you had Chief Irons around to take care of the town.” Doug Kistle admits that at the age of 12 he was a bit of a harmless prankster. He and his pals would go around on Mischief Night and ring door knockers with the aid of an attached fish line. When the door was opened, they’d break the line and run off. “He didn’t catch me putting it up; he just caught us walking in the road,” remembered the former Kistle fondly with a laugh. “He spotted something in my pocket and he asked, What’s that for?’ He didn’t do anything, he just told us to get home and get to bed. We were pretty mischievous kids when we ran around, but overall you never forgot who he was, and you respected him as the authority of the town, that’s for sure.” “He was quite a guy,” added Mike Krupa, another lifelong borough resident who remains a close friend of Kistle today. “He had a lot of control. He had a job to do, which was to clean up Franklin, and he did it well. The chief was a good man. He was very popular with the kids because he connected with the children. He went out of his way, and he made certain that we knew him. We knew Chief was a nice guy, but you didn’t fool around with him.” “He expressed the law in a way youngsters knew and appreciated,” Krupa said. “He protected the town and he protected the kids. We all respected him; there was a sense of respect and there was a sense of fear.” Fifty years later, however, things have changed. While the law enforcement of the early 21st century is better trained and equipped than ever before, it also must deal with both legal and political restraints. For that reason, if Chief Irons were around today, he might be dismayed by what’s going on, both Bene and Doug Kistle feel. “Back then, there wasn’t hardly any press at all and crime wasn’t high, but he always kept on the ball,” Kistle concluded earnestly. “I think he’d be frustrated today because he wouldn’t be able to get away with that today. He had full authority to do whatever he wanted to do. But today, between the press and the lawsuits, his hands would be tied.”